Hurricane Katrina struck the US Gulf Coast on August 29, 2005 as a category 3 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson scale, causing unprecedented damage to numerous Louisiana and Mississippi communities.Reference Knabb, Rhome and Brown1 During the hours and days after Hurricane Katrina, breaches in the levee infrastructure resulted in flooding throughout approximately 80% of New Orleans. A massive rescue and recovery effort was launched by local, state, and federal governments and nongovernmental organizations. Before Hurricane Katrina, the deadliest hurricane to make landfall in the United States during the previous 50 years was Hurricane Audrey (1957), with an estimated 416 deaths.2 Hurricane Andrew (1995), the last category 5 hurricane to strike the United States, caused 26 deaths.2 Although several preliminary estimates exist of the deaths attributable to Hurricane Katrina, 1,3,4 no prior report has systematically reviewed all of the available death databases to accurately document Hurricane Katrina mortality in Louisiana.

Our objectives were to verify and document the number of deaths from Hurricane Katrina among people in Louisiana at the time of the storm and to characterize the storm's mortality burden by victim demographics, geographic location, timeline, and cause of death. This report is the first to combine multiple death databases to assess the number of storm-related deaths among Louisiana residents and people who were in Louisiana at the time of the storm and to provide information regarding the causes of death. The findings in this report will aid public health and emergency preparedness efforts and may help reduce the mortality burden in future natural disasters.

METHODS

Data Sources

Data sources included the Hurricane Katrina Disaster Mortuary Operational Response Team (DMORT) database and death certificates collected through Louisiana vital statistics and out-of-state coroners' offices. DMORT is a federal response team that provides assistance with mortuary activities during disaster situations. Out-of-state death certificates of Louisiana residents during the period of August 27 to October 1, 2005, and others that state coroners deemed worth consideration for potential association with Hurricane Katrina were forwarded to the Louisiana coroner's office from coroners' offices in 26 states and the District of Columbia.

Katrina Classification

The primary classification of Katrina-related deaths assigned by parish (county) coroners on death certificates was International Classification of Diseases-10 code X37, victim of cataclysmic storm. The majority of deaths had multiple hierarchical cause-of-death classifications; however, if trauma, injury, or drowning was listed as a contributing cause of death, these victims were categorized as drowning or injury victims in our database. A systematic review of all of the records in the DMORT database and of Louisiana death certificates yielded a final database of confirmed victims. A number of quality-assurance cross-checks were conducted, including ensuring no duplication of records across data sources and date of death occurring within a plausible timeline (August 27–October 31, 2005) and within the geographic location for Katrina-related deaths (ie, death occurring in or victim evacuated from the affected southeastern Louisiana parishes). All deaths occurring before August 29, 2005 and after October 1, 2005 were reviewed to verify that Hurricane Katrina was listed as a contributing cause of death, and all of the deaths occurring after September 23, 2005 were reviewed to determine whether they were associated with Hurricane Rita, which struck southwest Louisiana on September 24, 2005. The final case definition for Katrina-related deaths in this analysis included all of the deaths in the DMORT database that were determined to be Katrina related, all Louisiana death certificates with victim of cataclysmic storm listed as the primary or a contributing cause of death, and out-of-state death certificates for Louisiana residents that were classified as related to Hurricane Katrina.

Data from Louisiana vital statistics were collected at the local levels through parish coroners' offices and then sent to the state level. Data from all 3 sources (DMORT, vital statistics, and out-of-state death certificates) were entered into an Access (Microsoft Corporation, Seattle, WA) database. Descriptive and inferential statistics were calculated using Stata version 9.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). We calculated age-, race-, and sex-specific mortality rates (per 10,000 population) for victims in Orleans, St Bernard, and Jefferson Parishes, where 95% of Katrina's victims resided. We conducted stratified analyses by parish of residence to compare differences between observed proportions of victim demographic characteristics (sex, race/ethnicity, and age) and expected values based on 2000 US Census data, using Pearson chi square and Fisher exact tests. We further stratified by race within each age category, where sufficient observations existed, to determine whether there was an age-specific effect of race among victims. We limited our comparative analyses to Orleans, St Bernard, and Jefferson Parishes.

Mapping Using Geographic Information Systems

To identify high-mortality geographic areas, Louisiana death records with addresses (n = 687) were geocoded using Environmental Systems Research Institute's ArcGIS version 9.2 (Redlands, CA). Most records were geocoded using the Environmental Systems Research Institute street file reference geospatial layer, which was used to match the address for location of death to the street file address. Records with only a nursing facility name were matched to the address of the nursing facility in the Homeland Security Infrastructure Program Public Health, Nursing Home geospatial layer.

Ethical Review

The study protocol was reviewed by the human subjects coordinator at the Office of Workforce and Career Development, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and determined to be a public health response that did not require further human subjects review.

RESULTS

We identified 971 Katrina-related deaths that occurred in Louisiana and at least 15 deaths that occurred among Louisiana Katrina evacuees in other states, for a conservative storm-related death total of 986 victims. The state coroner was forwarded 446 out-of-state death certificates for Louisiana residents. Of these, 15 were clearly related to Hurricane Katrina, and 431 were classified as indeterminate because no indication of hurricane association was listed on the death certificate. Our total mortality estimate of 986 victims likely represents a lower bound estimate for Katrina mortality in Louisiana. Including all deaths classified as indeterminate (DMORT, n = 23; and out-of-state, n = 431) yields an upper bound estimate of 1440. We limited all subsequent analyses to deaths we determined to be related to Hurricane Katrina (n = 986).

Cause of Death

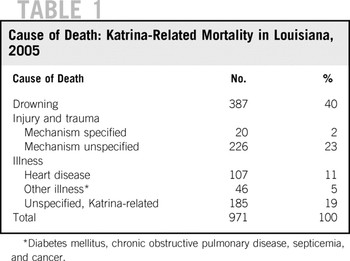

Excluding the 15 out-of-state deaths, we found that of the 971 people who died in Louisiana as a result of Hurricane Katrina, data on cause of death were available for 800 people. Three hundred eighty-seven victims drowned, and 246 people sustained trauma or injuries severe enough to cause their deaths. The mechanism of injury was unspecified for 226 trauma or injury deaths; specified injury-related causes of death included heat exposure (n = 6), unintentional firearms death (n = 4), homicide (n = 2), suicide (n = 4), gas poisoning (n = 3), and electrocution (n = 1; Table 1).

TABLE 1 Cause of Death: Katrina-Related Mortality in Louisiana, 2005

Victim Demographic Characteristics

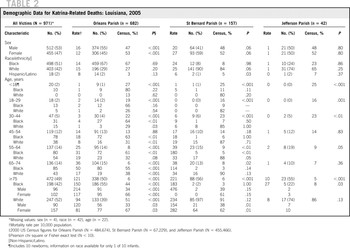

Among the 971 Hurricane Katrina victims who died in Louisiana, 512 (53%) were men; 498 (51%) were black (non-Hispanic/Latino); 403 (42%) were white (non-Hispanic/Latino), and 18 (2%) were Hispanic/Latino (Table 2). Other victim races included Asian (n = 4), American Indian (n = 4), and other (n = 1). Data on race/ethnicity were missing for 42 victims (4%), age was missing for 22 victims (2%), and sex was missing for 4 victims (<1%).

TABLE 2 Demographic Data for Katrina-Related Deaths: Louisiana, 2005

The mean age of Katrina victims was 69.0 years (95% confidence interval [CI], 67.8–70.2), and their age range was 0 to 102 years. Approximately 50% of the people who died as a result of Hurricane Katrina in Louisiana were 75 years old and older. Fewer than 10% of victims were younger than 45 years old. In Orleans Parish, where the majority of victims lived and died, all age categories of victims (except those 45–54 years old) were divergent from the overall parish age distribution of the population. The most dramatic difference occurred among people 75 years old and older (Pearson chi square [χ2] 2400; degrees of freedom (df) = 1; P < .0001; Table 3). In Orleans Parish, men were more affected (χ2 17.4, df = 1, P < .001), and women were less affected (χ2 18.7, df = 1, P < .001) by storm mortality, relative to their underlying population distributions. In both St Bernard and Jefferson Parishes, the sex and racial distributions of Katrina victims were not significantly different (P > .05) from census population figures for those parishes, except for Hispanic/Latino victims in St Bernard Parish (P = .03; Table 2).

TABLE 3 Place of Death or Where Body Was Found (N = 877)

In Orleans Parish, the mortality rate among blacks was 1.7 to 4 times higher than among whites for people 18 years old and older, indicating that the effect of age on mortality confounded the effect of race. Chi square and Fisher exact tests assessing differences in proportions of black and white victims within age groups found that blacks were significantly more likely to be storm victims than whites in all age group categories 30 years old and older in Orleans Parish (P < .05). Race-specific mortality rates were also higher among blacks 55 to 64 years old in St Bernard Parish and 75 years old and older in Jefferson Parish, but results from race- and age-specific stratified analyses in these 2 parishes are limited by small number of observations (n ≤ 5). Among the largest age cohort of victims (people 75 years old and older), we further stratified by both race and sex in Orleans and St Bernard Parishes and found that black men 75 years old and older were significantly overrepresented in Orleans Parish (P < .001; Table 2).

Timeline

Of 799 deaths in vital statistics records in which date of death was recorded, 650 (81%) occurred on August 29, 2005. Seven deaths occurred in the 2 days preceding the storm and 4 deaths occurred after October 31, 2005 (Fig. 1). For the 171 victims who were listed only in DMORT and for whom a date of death was not specified, date when victims were found was available for 129 people. The majority of these people (n = 82, 64%) were recovered during the second and third weeks after the storm (September 5–19, 2005).

FIGURE 1 Timeline of Hurricane Katrina-related deaths in Louisiana, vital statistics (N = 799)

Where Victims Lived and Died

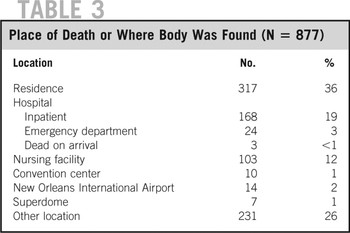

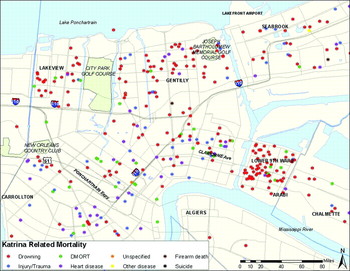

Data on parish of residence and parish of death were available for 934 and 854 people, respectively. The majority of hurricane victims lived in Orleans Parish (73%), followed by St Bernard (17%), Jefferson (5%), Plaquemines (1%), and St Tammany Parishes (1%). Victims died primarily in Orleans Parish (70%), St Bernard Parish (14%), Jefferson Parish (4%), and East Baton Rouge Parish (3%). Data on both parish of residence and death were available for 844 storm victims; more than 80% of these victims died in their parish of residence. Sixty-five percent of Hurricane Katrina victims in Louisiana died of injury or drowning. The majority of these deaths occurred in Eastern Orleans Parish, specifically the lower ninth ward; in Lakeview and Gentilly, adjacent to Lake Pontchartrain; and in St Bernard Parish (Figs. 2 and 3). Drowning and injury-related deaths occurred predominantly near levee infrastructure breaches.

FIGURE 2 Location of Hurricane Katrina deaths, southeast Louisiana, 2005 (N = 687)

FIGURE 3 Location of Hurricane Katrina deaths, Orleans Parish, 2005

Data related to place of death or where victims were found were available for 877 people (Table 3). Deaths or places where victims' bodies were recovered occurred predominantly in residences (36%), hospitals (22%), and nursing facilities (12%). More than 25% of victims (n = 262) were found in other locations, including roadways, the New Orleans airport, the Convention Center, and the Superdome. For the deaths recorded in the DMORT database only that did not have date of death available, it is unclear whether the person died at the location or the body was brought to the location after death. The date the body was found was available for 129 of 171 people that appear only in the DMORT database. Of these 129 people, 80 (62%) were recovered before September 15, 2005.

At least 70 people who were classified as hospital inpatients died during the period August 29, 2005 to September 2, 2005, in New Orleans hospitals and an additional 57 victims were recovered from New Orleans hospitals and brought to the DMORT facility from September 5 to 12, 2005. From August 29 to September 3, 2005, at least 71 people died in nursing facilities in Orleans, St Bernard, and Jefferson Parishes, and an additional 7 bodies were recovered from nursing facilities in these parishes during the weeks after Hurricane Katrina.

Out-of-State Deaths

The state coroner's office received 446 death certificates from 26 states and the District of Columbia for Louisiana residents who died from August 27 to October 1, 2005 and other death certificates that coroners' offices deemed worthy of consideration for potential association with Hurricane Katrina. The majority of out-of-state deaths occurred in Texas (221, 50%), followed by Alabama (47, 11%) and Mississippi (43, 10%). Of the 446 Louisiana residents who died out of state, 53% were female; 59% were white; and their mean age was 67.3 years (95% CI 65.3%–69.3%). The majority of evacuees had lived in Orleans Parish (40%), Jefferson Parish (22%), St Tammany Parish (5%), and St Bernard Parish (4%). Seventeen out-of-state deaths (4%) occurred among Calcasieu Parish residents, likely Hurricane Rita evacuees. Of the 446 deaths, only 15 people were classified as Katrina-related deaths by a state coroner and thus included in our final mortality count.

DISCUSSION

This report provides a conservative estimate of deaths that occurred in New Orleans and Louisiana associated with Hurricane Katrina. We document at least 971 Katrina-related deaths among people in Louisiana and 15 deaths among Louisiana Katrina evacuees. Older adults were clearly the most affected population cohort during Hurricane Katrina, particularly people 75 years old and older, who made up 49% of victims in Louisiana, whereas their age cohort represents fewer than 6% of both the greater New Orleans and the overall Louisiana population. Children and younger adults were underrepresented among storm victims relative to their proportional population size.

A total of 178 people 75 years old and older died in their homes, 115 of drowning. There are at least 2 possible explanations for these findings. The first is that older people may have been less likely to leave their homes during the storm evacuation because of prior experience with false alarms regarding the intensity and potential threat of a hurricane, fear of their abandoned homes being looted, or not wanting to be separated from medical or other routines. Another possible explanation is that older people are more likely to die of drowning and injury during a hurricane or flood and that comorbidities contribute to their vulnerability to storm-associated mortality. It is likely that both factors contributed to the disproportionate representation of people 75 years old and older among Katrina victims.

In the days following Hurricane Katrina, multiple large hospitals in New Orleans flooded and were reportedly operating without power or sanitation services in extreme heatReference Brinkley5 while ambient temperatures in the greater New Orleans area were ≥90°F (32°C) during the days and weeks following Hurricane Katrina.6 As a result of rapidly deteriorating conditions in the New Orleans hospitals and extreme difficulties in evacuating their existing patients, hospitals in the downtown New Orleans area were reportedly not admitting new patients in the days following the storm.Reference Brinkley5 At least 70 hospital inpatients died in New Orleans hospitals, and an additional 57 storm victims' bodies were recovered from hospitals in the days immediately following the storm, indicating that their storm-related cause of death occurred in the hospital. The power outages and dire conditions reported in certain New Orleans hospitals after the storm underscore the importance of disaster preparedness. Hospitals in hurricane-prone areas should ensure that adequate generators are available in elevated locations that are not prone to flooding. Water, food, and other supplies should be available to maximize the likelihood that patients using ventilators and other life-support interventions will survive if a similar emergency situation occurs. More than 70 people died in nursing facilities in Orleans, St Bernard, and Jefferson Parishes on August 29, 2005 and in the days immediately following Hurricane Katrina, indicating that more targeted emergency and disaster preparedness planning, especially with respect to evacuation capability, is needed for these types of institutions.

The overall proportions of deaths among non-Hispanic blacks and whites in the most affected parishes—Orleans, St Bernard, and Jefferson—were remarkably consistent with their pre-Katrina race/ethnicity distributions from the 2000 US Census (Table 2). However, stratified analyses evaluating the effect of race within age groups revealed that the dominant effect of age on overall storm mortality masked the differential effect of race in most age groups in Orleans Parish, where race-specific mortality rates were on average 2.5 times higher among blacks compared with whites. Older black people in Orleans Parish, particularly men, were disproportionately represented relative to their underlying population distribution. Of note, only 4 storm victims were Asian, although Asians make up 2% of the Orleans Parish population and 1% of the overall Louisiana population.7 Although Hispanic/Latino and Asian race/ethnic groups appear to have been less affected by storm mortality relative to their proportional population size, victim numbers in these groups are small, limiting statistical interpretation. Similarly, small numbers of observations (n ≤ 5) in our stratified analyses of race/ethnicity within age groups in St Bernard and Jefferson Parishes limited our ability to assess potential associations between demographic characteristics and mortality. The role of poverty in Katrina mortality is unclear because we did not have income data for victims, but socioeconomic status merits future research to determine whether age- and race-associated poverty may have increased the vulnerability of these populations or limited their ability to evacuate.

The primary strength of this study is the use of multiple death databases to systematically verify each death as related to Hurricane Katrina using consistent and specific criteria. Incorporating DMORT data allowed us to identify 171 victims who were not classified as Katrina related in vital statistics/death certificate data, including 17 victims whom coroners were unable to identify by DNA matching or other methods. In large-scale high-mortality disasters, DMORTs should be considered as an additional data source to better document mortality.

Limitations

This study is subject to a number of limitations. First, the disaster response aftermath of Hurricane Katrina may have limited the ability to precisely document all deaths. Although unlikely to be a large number, it is possible that some people who died during the storm were never found or documented. Second, classifying people who were evacuated and later died out of state from Katrina-related causes is inherently difficult, especially as regards older people who had serious preexisting medical conditions. It is unknown whether these people would have died had the storm occurred or not. It is also unknown whether the storm exacerbated preexisting medical conditions enough to lead to death. The majority of the 446 out-of-state deaths were from chronic medical conditions, primarily heart disease, respiratory disease, and cancer. The clearest association with Katrina in our review of out-of-state death certificates was 1 person whose body was found in the Gulf of Mexico off the Florida coast. His death certificate specified drowning while trying to save a family member who resided in the greater New Orleans area as the cause of death.

Determining whether Hurricane Katrina contributed to out-of-state deaths was particularly difficult in instances in which patients died in hospitals during the days and weeks following Katrina (n = 283), for suicides (n = 5), for accidents (n = 25) and for cases pending further investigation or toxicology reports (n = 15). The role of Hurricane Katrina in the majority of the 446 out-of-state deaths will probably never be clearly delineated because coroners in different states may have used different criteria for classifying victims as storm related. The 15 deaths with victim of cataclysmic storm or other Katrina-related indications on their death certificates almost certainly represent a lower bound estimate of out-of-state deaths among Louisiana Katrina evacuees.

Hurricane Katrina death data from Louisiana vital statistics first became available approximately 2 years after the storm. Instituting an electronic reporting system for recording death certificates would aid with timely use of data for both government and community preparedness and disaster response efforts.Reference Stephens, Grew and Chin8 Alternately, if existing technological infrastructure is unavailable, active mortality surveillance efforts should be initiated immediately to document deaths in the early stages of rescue and recovery responses, not only to aid with accurate mortality reporting and victim identification but also to mobilize needed resources (eg, body bags, mobile laboratories, morgues) in a timely manner.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite the above limitations, this report provides the most complete picture of Katrina-related mortality in Louisiana to date. At least 986 people in Louisiana died as a result of Hurricane Katrina, making it the deadliest hurricane to strike the US Gulf Coast in more than 75 years. To prevent hurricane-related mortality on this scale from occurring in the future, disaster preparedness efforts must focus on evacuating and caring for older people, including those residing in hospitals, long-term care facilities, and personal residences. Adequate mortality reporting in disaster settings, particularly when infrastructure has been damaged or destroyed, is vital to ensuring timely collection of mortality data. Rapid identification of vulnerable populations and risk factors during disasters will enable response teams to provide appropriate interventions to these populations and to prepare and implement preventive measures before the next disaster. Projections of a sustained or intensifying cycle of Atlantic Ocean hurricane activity throughout the coming decades9, Reference Trenberth and Shea10 and the unprecedented landfall of 2 category 5 storms (Dean and Felix) during the 2007 hurricane season underscore the critical need for all levels of government to be ready to evacuate and care for vulnerable populations during future storms.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank D. Bensyl, W.R. Daley, and D. Koo for useful comments on the manuscript.

Authors' Disclosures The authors report no conflicts of interest.